Comparing Android Build Times by CPU

23 August 2020

I know many in the community might crucify me for saying this, but I actually don’t mind using a Windows machine for Android development; especially if it’s my desktop. My two go-to tools are Android Studio and Affinity Designer, both of which run fine on Microsoft’s OS.

Very occasionally I’ve had the need to run a bash script, but in those instances Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) has been surprisingly capable. The only real loss for me from macOS is Keynote.

Much of this stems from my interest in PC gaming. The allure of high refresh rate displays, large game libraries, and affordable performance means that macOS isn’t an option. And I always figured that if I had the hardware for fun, I may as well put it to work too.

However the tool of choice for many Android developers seems to be a Macbook Pro, and I can see why. There’s a lot to like about them. The build quality (excepting keyboard) is superb, the screen is fantastic, and they provide a Unix environment without the hassle of needing to recompile your kernel to get wifi working. (Linux burnt me a little).

But when it came to working on my own Android projects, I assumed I was better off making use of my gaming PC. I knew that a desktop grade CPU would outperform a laptop CPU, so compile times would surely be better compared to a Macbook.

But just how much performance difference is there? What kind of CPU do you need in a desktop to outperform a laptop? Will any mid range CPU be better? What about a monster, productivity focused CPU? I decided to do some digging.

I’ll note that this is my first attempt at any such benchmark. I’m aware that many things can affect a benchmark of this nature, and it’s entirely possible that there are flaws in my methodology. I’ll try to be as clear as possible about the process I’ve taken. If anyone spots areas for improvement, I’d welcome the feedback. This is something I’d like to get better at.

With that out of the way, let’s discuss how I went about the tests.

Projects and Methodology

When measuring build times, I wanted to select three open source projects that represented different levels of complexity.

- Tivi: Lots of modules, decent amount of code

- commit

e9d71b84792d74c35bae38641c1620bc44a6f878

- commit

- Plaid: Some modules, medium amount of code

- commit

e703957b5e5d4728dea94f11f8d0d27d227f9725

- commit

- Socket Weather: One module, small amount of code

- commit

4ba5df8f1ad4cdceb0337cd2fff5af1010095079

- commit

With each of these projects, I tried to profile both full and incremental builds.

Full builds

After successfully completing a build of each project, I executed the following command five times:

gradle --profile --offline --rerun-tasks assembleDebug

Incremental builds

I modified their respective MainActivity files, adding a companion object.

companion object {

val test = "test"

fun test0() = test + "test0"

}

I incremented the number in both the function name and string between five compilations. This was an attempt to see how incremental compilation would cope with a static function changing in both signature and content. With each increment, I executed:

gradle --profile --offline assembleDebug

Once that was done, I took the Total Build Time in the generated profile reports of each build type. I calculated the median time of the five builds in each category, and it’s that value that’s shown in the results below.

CPUs tested

Unfortunately due to the global pandemic, I wasn’t able to test with as many CPUs (especially those in Macbooks) as I would like.

Desktop Core i7-8700K

This six core, twelve thread Intel processor from late 2017 still holds up well in 2020 for gaming.

Desktop Core i5-7500

Released at the beginning of 2017, this four core, four thread 7500 represented great value for gaming compared to its i7-7700 contemporary at the time.

Desktop Ryzen 3950X

Sixteen core, thirty-two thread powerhouse released at the end of 2019. This CPU was a huge boon for anyone looking to build a powerful workstation for tasks that could take advantage of many cores. While not cheap compared to other consumer processors, it’s considerably more affordable than the likes of Intel’s Xeon chips or AMD’s Threadripper series.

Desktop Ryzen 3600

Another six core, twelve thread CPU. Great value for both gaming and productivity released in mid 2019.

Laptop Core i9-8950HK

Yet another six core, twelve thread processor, this CPU was running in a 2018 Macbook. A machine infamous for its launch day overheating that was quickly addressed (mostly) by Apple.

Laptop Core i7-4960HQ

The grandfather of the bunch. A four core, eight thread CPU housed in a late 2013 Macbook that’s served me well over the years.

Results

Let’s start by looking at Socket Weather. A tiny project that these processors should eat for breakfast.

Under ten seconds for a full build on most CPUs! Great for an Android app (though maybe still a little slow 😏).

What you’ll notice here, and in all the following benchmarks, is that the i5-7500 stands out like a sore thumb.

This was quite a surprise. On paper, it compares closely to the older 4960HQ. Both have four cores, and both can boost to 3.8 Ghz. However unlike the mobile i7, the desktop i5 lacks hyperthreading.

I’m not convinced that this alone is enough to cause the 4960HQ to be 53% faster. If anyone in the community has other ideas for what might be causing the discrepancy, let me know!

Incremental build times of around one second. Amazing, but also to be expected for a project of that size. The desktop CPUs are definitely faster, but the difference is slight. Let’s see what happens when we build a larger project.

These kinds of times might be a little more familiar to Android developers. Here we can see the desktop processors making decent gains over their mobile counterparts; the i7-8700K being 28% faster than the i9-8950HK.

When building Plaid incrementally the times are tighter, but still noticeably different with the desktop i7 being 24% faster than the mobile i9.

Let’s dial it up to the largest project tested: Tivi.

Hopefully you don’t have to perform full builds of a project like Tivi too often! It was here that I fully expected to see the 3950X pull ahead and spread its wings.

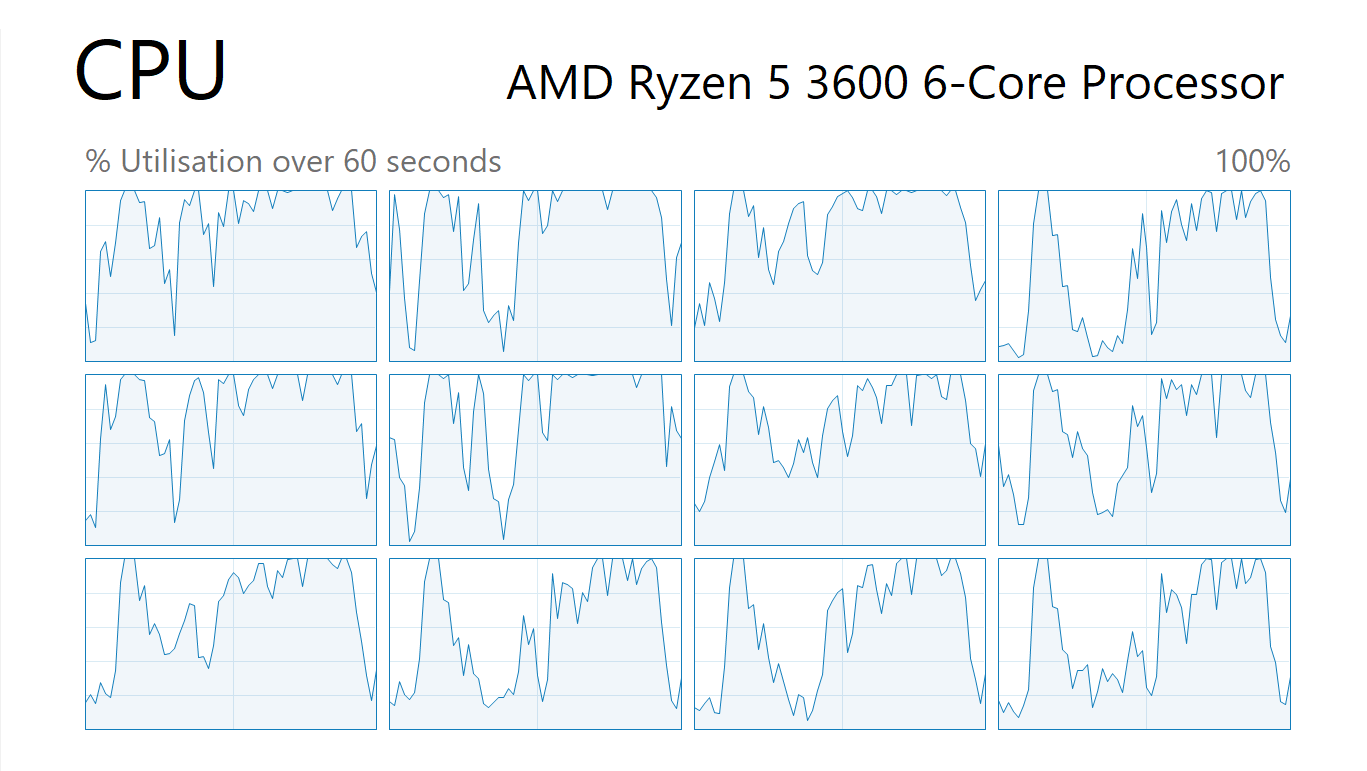

My reasoning came from looking at CPU utilisation on the 3600 during a full build of Tivi.

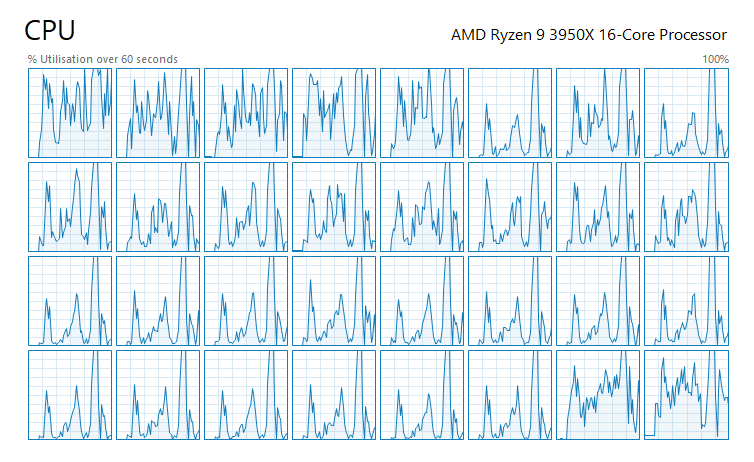

We can see periods where all twelve threads are fully utilised. I figured if all twelve get used, then perhaps another twenty would help.

But as we can see, that’s not quite how this project scales. There’s just not enough happening in parallel in order to make use of those cores. The 3950X is only 2.5% faster than the i7-8700K, suggesting that raw clock speed is still incredibly important when building a project like Tivi.

Comparing the i7-8700K to the i9-8950HK, the desktop chip provides a 35% improvement.

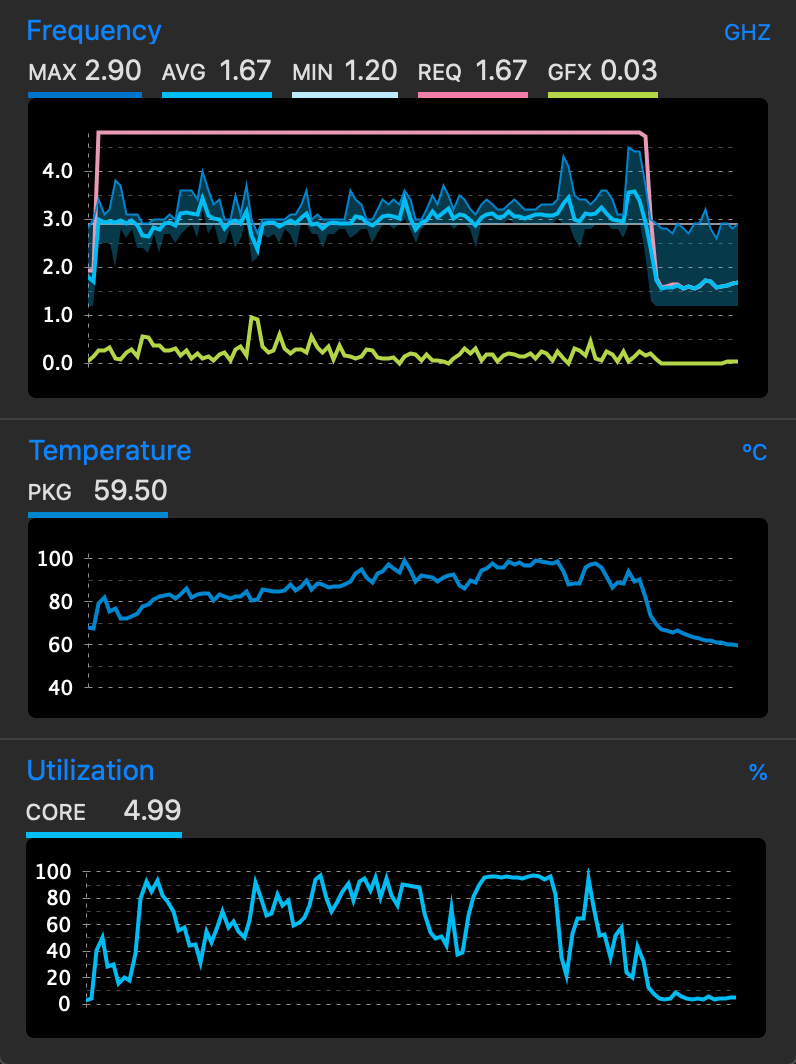

If we open Intel’s Power Gadget during a full build of Tivi on the 2018 Macbook, we can see there are a couple instances where the CPU hits 100°C.

This does make me wonder if we could eke out more performance if the processor had better cooling, but it didn’t seem like the average clock frequency suffered too much with the power settings Apple have in place.

I’m also not as keen as others might be to pull apart a Macbook and improve the cooling out of curiosity!

When performing incremental builds, our desktop processor lead isn’t anywhere near as pronounced. Better for sure, but even they can’t build Tivi quickly. One full rebuild of Socket Weather is faster than an incremental build of Tivi!

Conclusions

So what can we infer from this limited data set? Should Android developers race out and build beefy desktops if they already have a Macbook?

If you’re mainly executing incremental builds throughout the day, then it’s a question of how many. You might only see improvements of a second or two, but if you’re executing them thousands of times a day then the cumulative benefit might be worthwhile.

If you find yourself performing full builds, such as frequently swapping between branches while reviewing code, then it’s perhaps worth more consideration.

The other scenario might be that you already have the hardware in your home. If you don’t mind losing macOS and can live with Windows or Linux as a development environment, there’s definitely performance to be gained.

What makes this more viable is the global pandemic. Many of us are stuck working from home and don’t have need for the portability of a laptop. If you’re not going to be swapping between computers, maybe choose the one with more power.

What if you want a new Android development machine?

Unsurprisingly the Core i7-8700K and Ryzen 3600 consistently outperformed the Core i9-8950HK. At the time of writing the 3600 can be purchased new for $190 US. Amazing when you consider how well it performed in comparison. You certainly get far more compute power per dollar if you’re willing to sacrifice portability.

There are many more CPUs out there that could be tested, and it’s possible my usage of Gradle doesn’t tell the whole story, but hopefully this exercise was as interesting for others as it was for me!

— Chris Horner